- Home

- D. C. Pierson

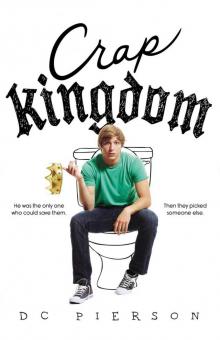

Crap Kingdom Page 3

Crap Kingdom Read online

Page 3

Tom swam past acid-washed jeans and a training bra. He felt the weight of his own waterlogged clothes. He suddenly became aware of the stuff in his pockets. The contents of his wallet would be soaked, and—oh dear God—his phone.

At pool parties he’d seen kids move to throw another kid in the pool, only to have the first kid say he had his phone in his pocket, and then the attacking kids, sympathetic because they, too, had phones in their pockets, would wait patiently while he removed his phone, keys, and wallet and set them on some patio furniture, and then, finally ready to be pranked, he’d get picked up and hurled in, stiffly, all the surprise gone. It was the least fun fun had ever been. But now Tom understood. His phone would most certainly be dead. And though not a lot of people called or texted Tom besides his mom and Kyle, he liked knowing that everyone had the option.

Tom breached the surface and still couldn’t see anything. Something had attached itself to his head, covering his eyes. He reached up and removed a pair of wet tighty-whiteys from his forehead. Then someone poured liquid soap in his face.

“Gargh!” Tom said.

“Ahhhh!” said the guy who had just poured soap in his face.

Tom immediately ducked back beneath the surface to wash the gross, waxy stuff out of his eyes. He resurfaced and saw the culprit: a man on a raft holding a bucket. Tom noticed another man on the raft. The other man noticed Tom.

“Thief!” he screamed, picking an oar up out of the water and rearing back, preparing to hit Tom’s head like a golf ball on a tee. “Clothes-thief!”

Gark popped up next to Tom.

“Hold on!” Gark said. “That’s the Chosen One! Official king’s business!”

Tom thought, These guys are gonna be so embarrassed when they realize they almost beheaded the Chosen One.

“Oh, that,” said the man holding the bucket.

The man holding the oar dropped his ready-to-kill stance and looked at his oar almost apologetically, like he felt guilty for promising it a head-whacking and then having to take it all back. He extended the oar to Tom.

“Here,” he said, and sighed. He hoisted Tom aboard, and Gark came next.

“I’m hereby commandeering this soaping vessel in the name of the king,” Gark said, “effective immediately! Bear us to port, where we may thence to the castle!”

The oarsman looked at his would-be-murdering oar as if to say, Get a load of this guy.

“Listen,” the bucket man said, “we got a job to do here. You’ll go in with us when we go in to refill, and that’s it.”

“Oh,” Gark said. “Well, in the name of the king, I command you to . . . do that!”

At last, Tom could keep his eyes open for longer than three seconds without fantastic pain. He took in their surroundings. They were in the middle of a lake dotted with islands and archipelagos of wet clothing. The water’s surface had the slick, rainbow-y look of bathwater. The oarsman steered toward a specific spot about fifteen feet away from where Tom and Gark had surfaced. The other man nodded for him to stop, and then poured out the last of the soap in his bucket. He tapped the bucket’s bottom a few times to make sure he’d used all of it.

“There,” he said, “Now we can go.”

Tom and Gark sat on one end of the raft and the two clothes-raft operators stood, simultaneously rowing and eyeing them. The one who’d been holding the bucket was wearing a Cincinnati Bengals jersey and leopard-print tights, and the man who’d tried to take Tom’s head off was shirtless and wearing swim trunks that were clearly meant to be worn by a six-year-old boy. They had a pattern of sharks swimming across them, but the guy was much bigger than a six-year-old, so the sharks were all bent out of shape, too big in places and too small in others, like they’d been swimming in radioactive waters.

The raft passed through small canyons between tiny waterlogged hills of twisted fabric. Tom marveled at the landmasses of wet clothes. He thought, What if this is somehow a way station for discarded clothing from all over Earth? What if it’s cast-off garments from all over the universe? He looked closely, hoping to see kimonos, or orange robes Tibetan monks might wear, or maybe, just maybe, alien fabrics of colors never before seen by human eyes.

He saw a pair of blue jeans, and the only thing alien about them was their enormous size. Mickey Mouse, wearing sunglasses, peered out at them from a T-shirt on the opposite wall of the canyon. They rowed into a larger bay. Clotheslines were strung across it, with jackets, shirts, sweaters, pairs of pants, and every kind of undergarment hanging from them, drip-drying. The sun broke through this jungle canopy every so often, and it was like a sun shower as they floated underneath the perpetual dripping of a hundred thousand pieces of throwaway clothing.

Women wearing outfits as mismatched as the raft guys’ stood on ladders placed precariously on the decks of larger rafts. They strung the clothes up, while more clothes were handed to them in baskets by men on rafts below. Tom watched as one of these women pulled a maroon rag out of a basket. It was twisted, the way guys would twist towels in locker rooms so they could whip each other. The only time Tom had seen this happen in real life was after freshman PE, and it was always halfhearted, like the guys involved didn’t really want to do it but thought they were supposed because they were in a locker room and that’s what you did, right? Maybe it happened more often, and with more enthusiasm, after actual competitive sporting events. Again, Tom would have to ask Kyle, his only real connection to the mysterious and sweaty world of athletics.

The woman untwisted the rag so she could hang it up, and as she did so, Tom realized that it was not a rag. It was, in fact, a T-shirt with ARROWVIEW printed in yellow on the front. Tom had been right to think of gym class. Here, however many million miles away, if the distance was even measurable in miles, was a woman hanging up a gym uniform from Tom’s high school. The clothes that bubbled up from the bottom of the lake weren’t from all over the universe or even all over the world. They seemed to be mostly from his town.

“Gark?” Tom said.

“Yes?”

“What happens to the clothes after you guys pull them out and dry them?”

“People buy them and wear them.”

“Ah,” Tom said.

“Or they used to, anyway,” Gark said. “Everyone pretty much has their thing that they wear now, so unless that thing falls apart, they’re set.”

“What if your thing that you wear gets dirty, and you want something else to wear while you clean the first thing?”

“I don’t understand,” Gark said.

“Well . . .” Tom felt weird being the position of defending laundry.

“I guess we haven’t picked up on a lot of the stuff about clothes yet,” Gark said. “They’re still a pretty new thing around here. You still get some old-timers who remember a time before this portal brought clothes in, and they like how it used to be, so they’ll just be, y’know . . .”

“Naked?” Tom said.

“Yeah,” Gark said.

“Good to know,” Tom said.

Tom spotted a skinny kid wearing an extra-extra-large T-shirt commemorating a church bake sale, standing on a little island of denim, his body pretty well hidden by hanging laundry. He was stuffing pairs of briefs into the pockets of his gym shorts. The oarsman saw him, too. He drew the bloodthirstier of the two oars out of the water, reared back, and whacked the kid with it. There was a wet smack and the kid went flying. The oarsman laughed. He looked back at Tom. Tom forced a close-mouthed smile. He didn’t want to display any knockout-able teeth.

“What do you call the thing that kid was grabbing?” Gark asked. “With, like, the stretchy stuff that goes around your waist?”

“Underwear?”

“Yeah,” Gark said. “Kids love that stuff. I don’t have much use for it myself.”

“Also good to know,” Tom said.

They reached a wooden dock. “Thanks for the lift,” Gark said. “I’m Gark, by the way.”

“I know,” said the oarsman.

“Oh! And this,” he said, becoming puffed up and grand, “is Tim.”

“Tom,” Tom said.

“Tom,” said Gark. “Well, can’t sit here all day chatting.” Gark hopped up and off the raft in one swift motion and, after his right foot got caught on a loose dock plank, fell down and got back up in six awkward motions. He turned and extended a hand to help Tom up onto the dock.

“You okay?” Tom said.

Gark nodded, wiping blood away from his nose with his other hand.

“Our transport awaits!” Gark said as he led Tom down a crisscrossing series of docks and gangplanks toward dry land. He’d said their modes of transportation were very different from the rental van, and Tom was excited to see exactly how different. Would it be a cart pulled by a weird four-legged pack-beast? Maybe the transport would just be the beast itself, and when Gark whistled it would lower its head, allowing them to climb aboard.

Tom had never realized he had so many expectations for fantasy worlds. Now that he was actually in one, he found that he had tons. One of the things he expected was a population of strange beings very unlike himself, whether they were reptile people or bird people or minotaurs in astronaut helmets. On the dock, though, he was surrounded by what appeared to be humans. No one had strange alien ridges on their noses or pointy elf ears, at least no one he’d seen so far.

Even in a world where everyone else was human as well, he expected to be stared at by strangers because of his out-of-place Earthly manner of dress. Yet as he and Gark walked through the crowd on the docks, no one stared at him, and it didn’t seem like it was because they were worried that he might melt them with his gaze or that they would be executed for daring to make eye contact with the Chosen One Whose Coming Was Foretold. It seemed like the reason no one was staring was that they had the same number of eyes and teeth and limbs he did and they were wearing clothes like his, from Earthly stores in Earthly malls, so they were indifferent to him just as he would be to a stranger he passed on the street who wasn’t attractive or famous or peeing their pants because they were crazy. A teenage girl with red hair and pretty green eyes passed them on their left and as she did so, Tom tried to catch her eye. It worked, but when she looked back at him she gave him a look he could’ve gotten from any girl in one of those Earthly malls. Great, he thought. I’ve been in this world for ten minutes and already at least one person thinks I’m a creep.

The dock became a path leading to the top of a hill. The sun was bright and hot, and there was only one of it, like on Earth, and it shone down from a sky that was blue, like on Earth, and these things were disappointing to Tom for reasons he couldn’t quite explain. But it was nice to be drying off in the sunshine. They reached the top of the hill. On the other side of the hill was a parking lot.

It wasn’t exactly like the parking lot in front of the Kmart, but the only differences were that the Kmart parking lot was paved and this one was just grass and dirt, and the Kmart parking lot had been mostly empty and this one was full.

It wasn’t full of sleeping griffins, either.

It was full of cars.

5

GARK HAD CLAIMED the vehicles in his world were vastly different than the ones in Tom’s world. It turned out he’d meant that the cars in his world were cars from Tom’s world but with a lot of trash stuck to them.

They found Gark’s car. Tom was not a car guy, but it looked to him like a windowless, mirrorless version of a 1980s sedan. Gark took Tom’s empty water bottle from the waistband of his pants. He reached into the car’s driver’s seat, pulled out a half-used roll of black electrical tape, bent down, and taped the bottle to the left front tire of the car. The tire was covered entirely in flattened, weathered bottles of various shapes and sizes. In fact it was made of them, Tom realized as he looked closer. It was like a tank tread made of water bottles and weathered, gooey straps of electrical tape. Gark stared proudly at this fresh new bottle, like it somehow made the makeshift tire complete. Tom noticed that every tire on every vehicle in the parking lot was like this. Some of the tires were made of crushed soda cans. The ones on the car across from Gark’s were made of grocery bags.

“Let’s go!” Gark said. He reached through the space where the driver’s side window would have been and pulled up on the tab to unlock the door, and then opened the door and climbed in. Tom did the same on his side. Gark had left the keys in the ignition.

Before starting the car, Gark leaned over and looked at a plastic cup that was fused into his dashboard cup holder. He noticed there were two inches of brownish liquid in the cup and said, “Perfect. I’m parched.”

“How long has that been in there?” Tom asked.

“Not long,” Gark said. “It’s just rainwater that collected while I was gone.” He put his hand through the space where the windshield would have been, demonstrating how the rain had reached the cup, and also how the one or two bugs in the water had gotten there as well. No wonder he thought he could just throw up while driving, Tom thought. In this world, it would’ve ended up outside the car.

Tom reached for his seat belt, only to discover that it had met the same fate as the tires, the mirrors, and the windshield. In its place were ten or so shoelaces hanging from one side of the passenger seat, each one spaced a few inches apart.

“You just tie those across you,” Gark said.

“Okay,” Tom said, reaching up to tie the top lace to the corresponding loop on the other side of his seat. He tried to lift his shoes up off the floor once he realized it was one big puddle of standing water.

Gark had accidentally tied two laces in the same loop. “Oops! Let me fix this, it’ll just take a second.”

Twenty minutes later, they were moving at last, crossing a grassy but otherwise featureless plain at a speed of maybe ten miles an hour. Tom looked over to see what their actual speed was but all of the needles on the dashboard panel that told you things like how fast you were going and how much fuel you had left weren’t there.

“Where did you get these cars?” Tom asked.

“They’re not cars,” Gark said. “They’re conveyances.”

“They’re cars,” Tom said.

“The parts came from your world,” Gark said, “but we combined them in our world, adding our own special touches.” To emphasize this, he leaned forward and took a sip from a very long straw that led to the dashboard-fused rainwater cup. He coughed.

“Where do you guys get the gasoline?”

“Oh, that stuff?” Gark asked. “We don’t have that here. That stuff is for cars. These are conveyances. They run on motion juice.”

“Is that just what you call gasoline?”

“No! Motion juice we make ourselves. It doesn’t have that annoying thing like gasoline where it runs all smooth. With motion juice—”

Bang! There was a small explosion behind Tom. He looked behind him out the no-window and saw a cone of fire pouring out of the gas tank.

“. . . it does that so you know it’s working,” Gark yelled over the roar of the flames.

“It’s supposed to do that?” Tom yelled.

“Yep,” Gark yelled, and smiled. “Motion juice!”

Tom looked back. The fire just kept coming out of the side of the car. Safety, he thought, was not a real concern here. He reached up and undid his top safety shoelace.

“Ooooh!” Gark yelled. “Rebel!”

They rounded a hill, and Gark’s village came into view. On its outskirts there were a few “conveyances” like Gark’s. Their still-burning vehicle drifted into a tight space between two other conveyances. It was so tight that Tom didn’t know how they were going to get out. Then he watched Gark turn the engine off and throw his door open with gusto, c

ausing the kind of metal-on-metal smacking sound that would have made Tom’s mom pull a piece of paper and a pen out of her purse so Tom could start writing the other car’s driver a note. Tom opened his door just as hard on his side. It banged the door next to him, hard. It was pretty fun.

The motion-juice fire had gone out, leaving a cloud of awful-smelling black smoke Tom had to wave away to breathe or see anything. Finally, he’d flapped his arms enough and got a good look at the village. It was mostly forts.

These were not the castle kind of forts. These were the kind of forts Tom would build in the living room when he was little and his parents were out for the night and there was a babysitter over, with a couple of kitchen chairs with a blanket strung over them to create a dark, private interior space. Sometimes he had even incorporated the couch, provided the babysitter was not asleep on it.

Here, in Gark’s village, tarps often stood in for blankets, and old doorless refrigerators or rusty smashed-open vending machines sometimes took the place of chairs. Some of the forts were made of actual blankets and chairs. The blankets were dirty and the chairs were beat up, and they had fully grown adults running in and out of them, conducting business, but that was really the only difference between them and the things Tom used to build and climb in to hide from imaginary enemies.

They walked into the village, dodging sleeping people in dirty thrift-store clothing and zigzagging between blankets strung over chairs placed back-to-back and a few feet apart.

“What is this place called?” Tom asked.

“Uhmm . . .” Gark said. “It’s not really called anything.”

“And what are you guys called?” Tom asked. “I mean, your people.”

“Good question!” Gark said. “Nothing in particular.”

Tom liked this idea a lot. He’d never thought about fantasy worlds as being on actual planets. He mostly thought of them as flat, two-dimensional maps stretched out on the first few pages of the book that detailed a hero’s adventures within that world. Tom preferred to think that this village, humble as it was, and the lake, soapy as it was, were the whole of this world. If there was a singing grotto or a Forest of Undoing around as well, he wouldn’t complain. But once you started naming things it indicated there were things beside the thing you were naming, because why would you name something if not to set it apart from something else, and once you started doing that, the world got a lot larger and less mystical and less innocent.

Crap Kingdom

Crap Kingdom